The W&M Blog

For admissions tips, career statistics and general thought leadership tidbits from the field, peruse our blog posts below.

Explores the mental health challenges veterans face and examines how specialized clinical training in military and veterans counseling strengthens the careers of those called to serve this vulnerable community

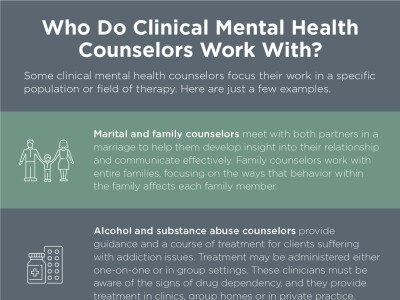

A clinical mental health counseling degree prepares professionals to fulfill an important need in their communities while promoting wellness and prevention access to care across diverse populations.

If you are looking for a purposeful, impactful career that helps people in need, clinical mental health counseling (CMHC) can be an extremely fulfilling choice. Learn how clinical mental health counseling (CMHC) programs prepare you for licensure and real-world practice through training and hands-on experience.

Discover what you'll study in a school counseling master's program—from foundational theories to hands-on training—and how this preparation equips you to transform students' lives.

Explore the essential competencies for contemporary school counseling, from interpersonal communication to career guidance and advocacy.

Learn how to design effective behavioral interventions in K–12 schools to promote positive conduct, reduce disruptions, and support student success.

Discover how school counseling programs promote student mental health, emotional well-being, and academic success through comprehensive support.

Explore the growing need for, and strategies for implementing, trauma-informed practices in schools.

Explore strategies for school counseling interventions to support student mental health and academic success. Earn W&M’s school counseling master’s online.

The days of your high school guidance counselor handing you a college application and sending you on your way are long gone. These days, school counselors are viewed as indispensable members of a school staff, with 93% of school counselors holding a master's degree.

Thoughtful and impactful counselors understand that it is critically important to develop a bond of trust and respect with their clients. It is this bond that frees clients to feel as though they can be open and vulnerable without fearing judgment or a betrayal of confidence.

Explore the vital role school counselors play in supporting student success and how to pursue a rewarding career in school counseling through William & Mary School of Education’s Online Master of Education in Counseling program.

What’s so appealing about counseling online that someone would seek it out or offer it if it weren’t absolutely necessary?

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) established the School Counselor of the Year award, which honors “professionals who devote their careers to advocating for the nation’s students and addressing their academic, career and social/emotional development.”

As a licensed professional counselor, you can create healing spaces for individuals recovering from trauma and help them develop strategies to improve their mental health and quality of life.

Each day, school counselors work with teachers and administrators to help students and their families navigate diverse challenges that affect students’ abilities to learn, develop and thrive—from academics and socialization to food insecurity, language barriers and mental health struggles.

How to Become a School Counselor: Educational and Professional Pathways to School Counseling Careers

A career path as a school counselor will be rich in its challenges and fulfilling in its rewards.

In addition to the experience and expertise you'll gain, online school counseling programs provide flexibility and convenience: You can study from anywhere, while keeping your current job, without being limited by geographic location.

Why is student mental health the concern of school counselors? A mental illness is a condition that impacts a young person’s thinking, emotions, and mood such that it interferes with his or her daily functioning at home and school.

Several factors can affect the total compensation for a school counselor. The salary number isn’t always the biggest consideration.

Decades of research supports a strong correlation between job satisfaction and life satisfaction. Career counselors facilitate this happiness by helping people find their dream jobs through assessments, evaluations and personalized advice.

Exploring non-traditional career options can help you find the right fit for your skill set and discover new passions.

As the need for mental health help continues to grow, so does the demand for counseling professionals in varied settings. Explore several opportunities and challenges that could be part of your future as a counselor.

School counselors play a vital role in the development of children and teenagers. These professionals help students navigate academic, emotional and social challenges.

Two students in William & Mary’s Online M.Ed. in Counseling program have been selected by the Tillman Foundation as 2022 Tillman Scholars. The prestigious scholarship, founded by the family of Pat Tillman, annually recognizes military service members, veterans and spouses who demonstrate extraordinary commitment to service, scholarship, humble leadership and impact.

Social workers and counselors share many similarities and make some of the most valuable contributions to society. Learn the differences between social worker and counselor careers.

Explore reasons to become a school counselor, the teacher’s skills that will help you succeed in your new position, and the credentials you need to make the career switch.

Two students in William & Mary’s Online M.Ed. in Counseling program have been selected by the Tillman Foundation as 2022 Tillman Scholars. The prestigious scholarship, founded by the family of Pat Tillman, annually recognizes military service members, veterans and spouses who demonstrate extraordinary commitment to service, scholarship, humble leadership and impact.

Delve into the crucial role of curriculum development as we unravel the multifaceted landscape of curriculum decisions and their impact on students and teachers.

What are the symptoms of PTSD in veterans and what treatments are available to help them cope? Explore the treatment options for veterans diagnosed with PTSD.

Explore the types of veterans assistance available to veterans suffering from PTSD, and learn more about how counselors can specialize in working with active military and veterans to make a positive difference to this population.

Drafting a personal statement for graduate school can be a challenging prospect for even the most confident writers. To make this process less daunting, let’s break it down into actionable steps that will help you shine.

Explore special education master’s degree specializations. There are several areas of special education master’s specializations that drill down to meet the needs of specific populations.

Let’s explore in greater depth how trauma counselors can work to the benefit of veterans. A trauma counselor works with clients who have been through a traumatic event in their lives and helps them find healthy ways to cope.

William & Mary experts discuss what the 6 principles of trauma informed care and how counselors can implement them.

Tuition reimbursement programs can offer significant help in managing the costs of graduate school. But what is tuition reimbursement?

In counseling, the relational depth between you and your client is of the utmost importance. Developing a strong and trusting relationship formed with evidence-based practices matters greatly, because the better the relationship, the greater the likelihood that your client will experience positive results.

If you’re just beginning to explore grad school application deadlines, you may be surprised to learn that the academic calendar at the graduate level may not be quite as rigid as you remember it from your undergraduate years.

Check out our infographic detailing tips for succeeding in a counseling internship, and prepare yourself for a meaningful, transformational experience.

We’ve collected some of the key questions grad school applicants have as they set about requesting recommendation letters, and we’ve provided answers that we hope you’ll find thoughtful and helpful as you work on your application for the Online Master of Education (M.Ed.) in Counseling.

The Skill of Self-Disclosure

Self-disclosure refers generally to a counselor’s sharing of personal information to clients during or outside the counseling session. Types of counselor self-disclosure can range from the sharing of information about the counselor’s personal life and experiences to the sharing of his or her personal opinions about particular issues and events.

Like many professionals, school counselors benefit from an environment in which they can communicate and collaborate regularly with their peers. Read about 5 school counselor blogs that offer advice and resources that can make a difference.

Explore 10 professional counseling organizations that may have particular relevance for a broad range of professional counselors and others who are considering a career in the counseling field.

Military and veterans counselors provide crucial support and coping tools to a population that arguably needs mental health care more than any other in the U.S. Learn how to help veterans, active-duty service members and military families address the harrowing mental health issues that can arise from military service,

Thinking of becoming a licensed professional counselor? Learn how a master's degree in professional counseling can help you reach your goals.

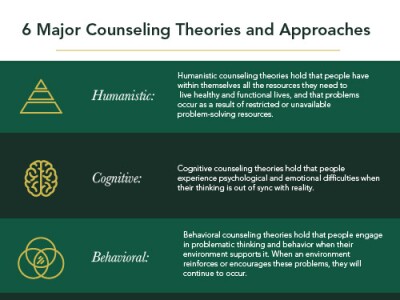

Explore essential counseling theories and approaches with William & Mary's guide. Understand client care dynamics to enhance therapeutic outcomes.

You need a master’s to be a counselor. Explore school counselor salary info, mental health counselor salary info and job growth for the field.

To understand many people’s continuing hesitancy to seek professional counseling, it is helpful to look at the history of mental health services before and after the Community Mental Health Act of 1963.

Choosing the right type of counseling degree is crucial to ensuring you provide skillful care to future clients and find professional and personal fulfillment. No pressure, right?

If you are interested in becoming a professional counselor, you have probably heard the acronym "CACREP" or the phrase "CACREP accreditation." So what is CACREP, and how does CACREP accreditation benefit counseling students?

The William & Mary School of Education is proud to announce a new Military and Veterans Counseling specialization within its CACREP-accredited Online Master of Education (M.Ed.) in Counseling program.

Social justice counseling has been referenced as the “fifth force” in counseling (Ratts, 2009). Such a worldview requires counselors to act as change agents through collaborative efforts in a multilevel framework and active engagement with the local community to achieve a more just world.

If you are a working professional or an individual who requires a certain amount of flexibility in your graduate coursework, an online counseling degree can help you pursue your passion without putting your life on hold.

Explore the rich history of school counseling and learn how counseling models and theories have evolved over time from William & Mary.

Years of counseling research catalogs the symptoms, causes and potential remedies for burnout. It is a concept all practitioners—in Clinical Mental Health Counseling, Military and Veterans Counseling and School Counseling—need to be aware of if they are to provide consistent, quality services to their clients.

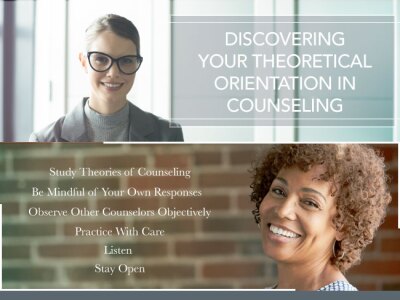

The history of the psychotherapeutic professions is defined by theories that have been proposed for how best to understand human behavior. Understanding the theories themselves is vital, but understanding and developing your personal theoretical orientation in counseling is just as, if not more, important.

Rip McAdams, professor in the Online M.Ed. in Counseling program at William & Mary, pens a personal essay on his journey from Navy SEAL to counselor.

During the past decade, some important achievements have been made that greatly benefit the work of clinical mental health counselors. Explore critical advances in clinical mental health counseling licensure standards and best practices.

The Locke-Paisley Outstanding Mentoring Award was given to Patrick Mullen, assistant professor of counselor education in the William & Mary School of Education, during the Southern Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (SACES) annual conference in Myrtle Beach Oct 11-13, 2018.

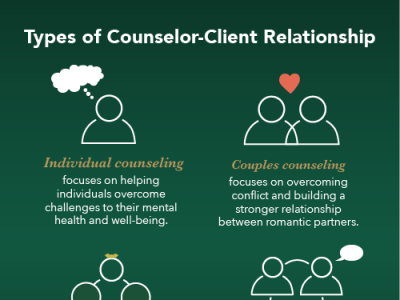

The American Counseling Association (ACA) defines counseling as the process of building therapeutic relationships that help individuals reach goals in their mental health, education and/or careers. Counseling is a collaborative partnership between counselor and client, in which the client can be an individual, couple, family or group.

Explore a few tried-and-true adjustments that you can make to your resume to ensure you give the best impression when submitting your graduate application.

If you are called to serve others, then perhaps you’ve already made the choice to become a counselor. Even so, you may be wondering what the job prospects are for you if you pursue a career in this field.

While clinical mental health counselors may work in a clinical setting, they work toward equipping their clients with strategies and frameworks to help them encounter life in mentally healthy ways

As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, proficiency in multicultural counseling is becoming a critical component in the training of new counselors. Learn how important it is for counselors to be culturally competent in their everyday roles.

William & Mary Prepares the Next Generation of Counselors With Our New Online Graduate Program